Artículos libres

Between care needs and organizational issues, the Royal Hospital of San Giacomo degli Spagnoli of Palermo (1680-1685)

Entre necesidades asistenciales y cuestiones organizativas, el Hospital Real de San Giacomo degli Spagnoli de Palermo (1680-1685)

Between care needs and organizational issues, the Royal Hospital of San Giacomo degli Spagnoli of Palermo (1680-1685)

Prohistoria. Historia, políticas de la historia, núm. 41, 1-25, 2024

Prohistoria Ediciones

Recepción: 01 Abril 2023

Aprobación: 05 Julio 2023

Abstract: Care structures in the modern age have undergone profound transformations due to the changed operating environment and advances in medical technology. In this sense, military hospitals are an essential part of this modernization. The Royal Hospital of San Giacomo degli Spagnoli in Palermo represents a significant case for analysing the processes of organizational and functional transformation that affected hospital structures in the second half of the 17th century.

Keywords: Military Hospital, Palermo, Organization, Care needs, Accountability.

Resumen: Las estructuras asistenciales de la era moderna experimentaron profundas transformaciones debido al cambio del entorno operativo y a los avances de la tecnología médica. En este sentido, es posible considerar los hospitales militares una parte importante de esta modernización. El caso del Hospital Real de San Giacomo degli Spagnoli de Palermo representa un caso significativo para analizar los procesos de transformación organizativa y funcional que afectaron a las estructuras hospitalarias en la segunda mitad del siglo XVII.

Palabras clave: Hospital Militar, Palermo, Organización, Necesidades asistenciales, Responsabilidad.

Introduction

The concept of hospitality can be traced back to the charitable ethic that propagated in the Middle Ages - especially during the spread of pilgrimages to the Holy Land and the crusades that followed - and which saw the religious orders as protagonists and, later, the laity, who supported the functioning of the first hospital structures with donations and legacies. In this context, hospitals were spaces where charitable assistance activities were carried out for the indigent and the sick, who shared many difficulties without a fundamental distinction between people needing medical care because they were ill and people in need because they were poor or derelict. From this point of view, the hospital should be understood in the Latin sense of the term as hospitium, shelter, or free asylum. A further explanation for the spread of hospital facilities during the central centuries of the Middle Ages is found in the urbanization process affecting the whole of Europe: the inadequacy of city structures had accentuated the problems of urban poverty and, consequently, of care.

The peculiar reasons that led to the creation of hospitals meant that they were places where the sick and the destitute could be accommodated indifferently, so there was no separation between the different types of 'in-patients' since the primary purpose was to hospitalize and not to cure (Cipolla, 1985: 51-70). This system did not withstand the impact caused by the great plagues of the 14th century; the increase in the number of sick –due to the epidemic proportions of the contagion– rapidly led the hospital structures in Europe to saturation and collapse (Stevens Crawshaw, 2012). The need to stop the phenomenon gave rise to the first organic health measures aimed, in some way, at regulating 'urban metabolism,' protecting public health, paying greater attention to hygiene and the behaviour of individuals, and following what could be considered the prodromes of modern health policy (Picardi, 2010: 329-335). The creation of special lay magistracies for the administration and supervision of public health immediately highlighted the conflicting aspects with the existing ecclesiastical hospital foundations, over which the church naturally claimed exclusive pre-eminence (Cipolla, 1985: 185). Likewise worthy of note are the foundations of national hospitals, in particular military hospitals, which eschewed the logic of urban control typical of city hospitals to become an operational instrument of the viceroyalty power within a broader welfare policy in favour of the troops that also included, for example, quarters or the supply of foodstuffs. Military hospitals, which came into being mainly between the 16th and 17th centuries, could enjoy a sort of 'backwardness advantage,' benefiting directly from the ongoing modernization process in other health facilities (Novi Chavarria, 2020: 22-40). This operation passed through a process of secularisation of the administrative bodies of the hospital institutions, reversing within them the role exercised by the laity and that exercised by the clergy (Bigoni et al., 2013: 567-594). This was achieved by employing a clear distinction between health care functions delegated to medical personnel, administrative functions to be performed by accountants and professionals, and, finally, religious care, previously prevalent, left to the care of the clergy (Riva & Cesana, 2013: 1-4).

The Royal Hospital of San Giacomo degli Spagnoli was founded in Palermo in 1560, with the consent of Pope Pius IV, when the Spanish nation, having no hospital of its own in Palermo to care for sick soldiers, used the ancient monastery and church of St James la Mazara.[1] The foundation took place following the sale –on 8 March of the same year– of the pre-existing hospital structure by the Regulars of St George to the Spanish government in exchange for an annual income of ten ounces.[2] The process of founding military hospitals for the troops stationed in the various territories of the Spanish monarchy had taken hold in the mid-sixteenth century, responding to a demand for identity on the part of Spanish communities outside the Iberian Peninsula and the strategic need to ensure medical support for the troops (Novi Chavarria, 2020: 22-26).

The hospital was located “all’angolo del quartero delle milizie spagnuole, che guarda il Papireto” (corner of the quarter of the Spanish militia, which overlooks the Papyretus), but twenty years later, the Viceroy Diego Enríquez de Guzmán, Count of Alba de Liste, considering the building cramped and unsuitable, ordered it to be moved to the front of the royal palace, also within the same quarter (Di Blasi, 1842: 251). The de Guzman's request, formalized on 7 August 1588 by the deputies of the Royal Hospital of San Giacomo, was approved at the session of the Civic Council on the following 31 August, during which a grant of three thousand ounces was approved for the reclamation of the Papireto marshes. The land needed to build the new hospital was granted.[3] However, the concession was not followed by the immediate construction of the new building. In fact: "after the building was interrupted, it was resumed after many years by the Viceroy Count of Castro of this city in 1622, who brought the size of the building up to a good standard, so that he is acclaimed as the founder of this hospital rather than a continuator [...] Don Stefano de Muniera, a Spaniard of the Order of Mercy, who was later bishop of Cefalù, was the promoter of this new building [...] The entire perfection of this hospital, however, is due to Prince Emanuele Filiberto of Savoy, Viceroy of Sicily" (Mongitore, 1723: 411).

From then on, the area around the hospital became the military quarter of San Giacomo. The hospital's activities continued until 1832—the year it was suppressed—and after national unification, the building was annexed to the adjoining Prefecture and Provincial Palace (Mazzè, 1998: 366).

The organization of the Royal Hospital of San Giacomo

Analysing book 716 of the “Secretarías Provinciales” Sicily fonds, kept at the Archivo General de Simancas 4, can highlight some fundamental aspects of the Royal Hospital of San Giacomo's management and internal organization. The hospital's management was entrusted to a deputation of six members appointed by the Viceroy, generally chosen from among those who had already held military or administrative posts.[4] In 1685, the deputies were as follows:

- Don Joseph de Bustos, sergeant major of the fixed tercio of the kingdom of Sicily;

- Don Luis Ossorio Carrillo marquis of Añalista, knight of the order of Santiago and veedor general of the gente di guerra of the kingdom of Sicily;

- Don Duarte Correa de Castel Blanco, Fieldmaster of the fixed tercio of the kingdom of Sicily;

- Don Juan Barbosa, Fieldmaster and Castellan del Castellammare di Palermo;

- Principe della Torre, Rationale of Real Patrimonio (Treasury) of the kingdom of Sicily;

- Don Juan de Retana, Conservador of Real Patrimonio (Treasury) of the kingdom of Sicily.

The deputation took care of the hospital's administration and managed the collection of annuities on the communities (universitates) of Trapani, Mazara, Agrigento, and Chiusa Sclafani, and on the spoils of vacant ecclesiastical seats, which would be used for the maintenance of the sick and to adorn the adjacent church.[5] In addition, his opinion was required to elect certain officers: butler, rationale, chaplains, and guardaroba (literally: garderobe). The latter, in addition to collaborating with the deputation to ensure the regular inflow of annuities, controlled the receipts and disbursements of the Tavola (a public bank in Palermo that acted as the hospital's treasurer) and ensured that the effects and money of the sick, deposited upon admission, were returned to them in full upon discharge. The entire hospital staff was referred to as a “family”.[6]

The chaplains of the infirmary and the church of San Giacomo la Mazara (respectively Don Gaspar Mohaber, elected on 9 June 1673, and Don Gaspar Caramara, elected in August 1682) devoted themselves to the pastoral care of the sick, always accompanied by the Maggiordomo, who had to ensure that the rooms were adequately cleaned and heated and that the infirmary was equipped with everything necessary; to this end, he checked the expense book daily and noted the purchase of medicines in it, on the recommendation of the nurse.[7] In this sense, the San Giacomo hospital conformed to the more modern concept of care construction spreading throughout Europe.[8]

The maggiordomo's notes were further checked by the rationale (accounting administrator) –chosen from among the alfieri riformati, the officers of the general veeduría or the principal contaduria, all accounting officers of the viceroy's tax administration– who supervised the hospital's entire budget. Every first of the month, referring to the nurse's book signed by the butler, he would account to the dispensary for all expenses incurred, record with the collector the month's receipts and disbursements, and ensure that debts were gradually paid off. To carry out these tasks, the rationale used the support of a coadjutor, especially concerning checking and signing the book of officers and servants, in which the duration of their service and the payment of wages were recorded. Finally, in the event of the maggiordomo’s absence, the rationale would take over the entire management of the hospital, with the collaboration of the deputy elected prior to the month, whose main task was to visit the sick and see that they were given proper care.[9]

The efficient functioning of the hospital also required the presence of orderlies, whose work was carried out under the strict control of the maggiordomo; the Massaro accompanied the sick to the relative ward, and the coricamalati saw to it that a doctor examined them to ascertain the pathology and arrange for their admission.[10] In the case of admission, the sick person underwent thorough personal hygiene and was provided with clean clothes supplied by the hospital itself (Bonaffini, 1980: 37). The remediante (apothecary) administered the medicines, while the dispensiero y comprador distributed the food to the sick and provided for the purchase of small expenses ordered by the father nurse. Each in-patient was allocated a bed with clean linen and blankets as well as a bowl for medicines, a towel for personal hygiene, and copper cutlery (Pidone, 1834: 16). The composition of the so-called “family” was completed by a pratico (a doctor who had not attended a university course but had acquired specific skills through experience), the church sacristan, a cook, three mozzi (servants), three apprentices, a repostero (baker), a laundress and a maestro d’acqua (a plumber in charge of maintenance work on the installations). There was also a judge, a lawyer with jurisdiction over civil and criminal cases, possible litigation, and a notary necessary for drafting wills. Finally, as in all hospitals in the city, the confreres of the Company of St. Maria della Consolazione served spiritual assistance, dispensing communion and providing confessions to the sick. In addition, the confreres devoted themselves to certain practical activities such as making beds, washing the feet of the wounded with hot water, distributing food, and tidying up the infirmaries (Mazzè, 1998: 368).

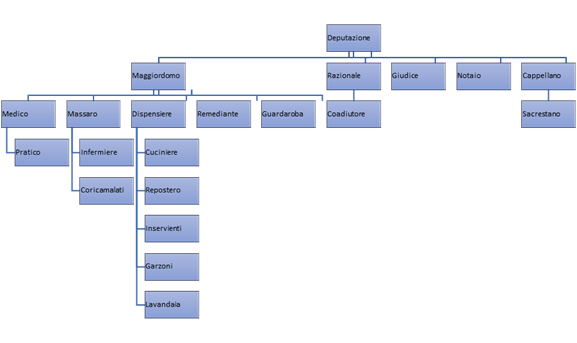

Figure 1

Royal Hospital of San Giacomo organization diagram

Author's elaboration on AGS data, SP, Libro 716

Diagram 1 shows a certain degree of modernity in the organization of San Giacomo’s Hospital, highlighting the clear division between operational (care and logistical) and administrative functions. The deputation coordinated, exercising control over all operations through the maggiordomo. This official not only organized care procedures but also provided for supplies and the needs of staff and patients. Unlike the other Sicilian hospitals, the figure of the hospitalier, who in the other city institutions performed the functions of administration and coordination, is not present in that of San Giacomo. The different organizational schemes can probably be attributed to the military origin of the hospital. The maggiordomo’s administrative activities, recorded in a particular account book, were checked monthly by the rationale. The same rationale was responsible for keeping all the hospital's accounts and compiling and updating the ledger. The rationale, judge (lawyer), and notary depended directly on the Deputation, not subject to the maggiordomo.[11] This peculiarity would suggest a desire to separate administrative tasks from other activities. The duties and functions of the rationale would be more clearly specified during the 17th century, in line with what happened in other Sicilian hospitals at the time (Rossi, 2014).

Treatment and nutrition

The archive documents do not mention the specifics of the therapies adopted, except the estufas y unciones to which some sick people were subjected during two periods of the five years –precisely from 7 April to 31 June 1683 and from 6 April to 15 July 1685– to cure them of infectious, rheumatic and respiratory diseases. The notation is probably due to accounting requirements arising from recording expenses incurred. The term estufas referred to rooms with large braziers, with a function comparable to today's sauna, where the sick were subjected to sweat baths, “aunque los que padecían algunas enfermedades infecto-contagiosas, como la sífilis, recibían el tratamiento en unas curiosas cajas o toneles de uso individual” (Gracia Rivas, 2006: 779). On the other hand, the unciones (ointments) were applied with mustard compresses to facilitate blood circulation and treat infections. Between April and June 1683, 57 soldiers were subjected to such treatments; to meet the necessary expenses, the Viceroy Count of Santo Stefano ordered a payment of 400 ounces.

| Period | Items | Amount | |

| April 1683 | |||

| Ordinary expenses | 26.24.12 | ||

| Estufero Tommaso Corrao | 107 | ||

| Apothecary | 50 | ||

| Buying 623 canne of fabric for sheet and pillows. | 115 | ||

| Buying 4 quintals of wool for mattresses | 19 | ||

| Buying 54 chickens at 12 grani each | 0.4.22 | ||

| Buying 449 canne of fabrico for 200 jackets at 15 grani for canna | 71.5.2.3 | ||

| Buying 70 canne of fabric at 4 tarì e 10 grani for canna to realize 21 jackets. | 9 | ||

| for sewing work of jackets. | 3.20.10 | ||

| Buying 49 canne of blue fabric for cloacks. | 6.5.10 | ||

| Buying 156 canne of fabric for 50 bedcovers. | 15.18 | ||

| For sewing works of mattresses and bedcovers. | 1.13.18 | ||

| Buying 73 tables e 30 feet for beds | 8.23 | ||

| Transportation costs | 0.10 | ||

| Sage infusion production | 3.1.12 | ||

| Boticario (pharmacist) | 50 | ||

| Total | 327 | ||

| May 1683 | 86.29.3 | ||

| June 1683 | 70.7.11 | ||

| Total period | 484.15.6 | ||

| April 1685 | Ordinary expenses | 55.29.1 | |

| Extra ordinary expenses | 12.13 | ||

| For chickens | 11.16.14 | ||

| Estufero | 40.2 | ||

| Speziale (apothecary) | 17 | ||

| Dispensero | 12 | ||

| Total | 149.0.15 | ||

| May 1685 | Ordinary expenses | 76.21.12 | |

| Estufero | 30 | ||

| Boticario (apothecary) | 20 | ||

| Buying 104 chickens at 2 tarì each | 19.2.12 | ||

| Total | 145.24.3 | ||

| June 1685 | Ordinary expenses | 80.28.5 | |

| Buying chairs | 0.29 | ||

| Buying 363 chickens | 33.27.2 | ||

| Sage infusion production | 0.17 | ||

| Total | 114.16 | ||

| July 1685 | Ordinary expenses | 28.28.18 | |

| Buying 69 chickens at 2 tarì each. | 6.13.14 | ||

| Estufero | 1.6 | ||

| Total | 36.17 | ||

| Total period | 409.27.18 |

For 1683, 84 ounces between the viceroy's original funding and the expenses incurred were covered by a supplement ordered by the Count of Santo Stefano himself. For the cures carried out from April to July 1685, on the other hand, the viceroy decided to devolve part of the funds obtained from the selling of the vacant ecclesiastical seats: 50 ounces in April, 100 in both May and June, while the 50 ounces in July were obtained from the hospital's credits. On this occasion, the funds allocated for care also needed to be increased, but unlike in 1683, no further payment order was issued, and the hospital entered the 68-ounce debt in its balance sheet as a debt. The loss would be replenished in instalments over the following months by pledging other hospital revenues.

Therapy was not limited to medical care; proper nutrition was also considered fundamental to recovering the sick.[12] The in-patients were given two meals. The type was determined daily by the doctor, depending on the illness, they had to be light and nutritious and consisted mainly of chicken broth, pasta, white meat (and in much smaller quantities also red meat), bread, and vegetables (Reinarz, 2016: 1-12). The list of daily expenses for June 1685 shows that fish consumption was utterly absent. Instead, eggs, sultanas, and fruit syrup were present. The diet was monotonous, however, and averaged a daily per capita consumption of ¼ chicken, 0.14 rotoli of red meat (about 110 grams), 3 ½ sandwiches, about 35 cl of wine as well as vegetables seasoned with oil and vinegar, ½ an egg as well as small quantities of milk, sweets, candied fruit (pumpkin) and dried fruit (almost exclusively almonds).[13] The amount of wine consumed coincides with estimates made by Maurice Aymard, according to whom 0.375 litres of wine per capita was consumed in Sicily in the 1780s (Aymard & Bresc, 1975: 596)[14].

Table 2 allows us to analyse the quantities of food purchased daily in June 1685 for several inmates, ranging from a minimum of 46 to a maximum of 67.

| Day | Bread (num.) | Meat(rot.) | Chicken(num.) | Livers(num.) | Offal(num.) | Winequarti | Olive Oil(rot.) | Pasta(rot.) | Semolina(rot.) | Wood(rot.) | Charcoal(rot.) |

| 1 | 192 | 7.3 | 13 ¾ | 0 | 3 | 18 | 2.10 | 1.9 | 1.9 | 40 | 2.3 |

| 2 | 187 | 6.6 | 14 ¼ | 2 | 4 | 17 ½ | 2.7 | 1.9 | 1.9 | 40 | 2.3 |

| 3 | 181 | 7.6 | 17 | 3 | 2 | 17. 3 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 40 | 2.3 |

| 4 | 205 | 7.9 | 15 | 2 | 4 | 24.3 | 2.11 | 1.9 | 1.9 | 40 | 2.3 |

| 5 | 221 | 8 | 13 | 3 | 4 | 23 | 3.1 | 2 | 2 | 40 | 2.3 |

| 6 | 233 | 9.6 | 14 | 4 | 8 | 23 | 3.2 | 2.3 | 2 | 40 | 2.3 |

| 7 | 201 | 10 | 14 | 2 | 2 | 18.1 | 2.10 | 2.3 | 2.3 | 40 | 2.3 |

| 8 | 230 | 8.3 | 15.1 | 8 | 2 | 21.1 | 2.11 | 2 | 2 | 40 | 2.1 |

| 9 | 196 | 8 | 17 | 2 | 2 | 24.2 | 3.2 | 1.9 | 1.9 | 40 | 2.3 |

| 10 | 201 | 8 | 16.1 | 4 | 4 | 19 | 3.1 | 1.10 | 1.10 | 40 | 3.1 |

| 2047 | 77.9 | 149.2 | 30 | 35 | 208.2 | 29.7 | 19.4 | 19.1 | 3 80 | 1.11.2 | |

| 11 | 200 | 8.6 | 16 | 5 | 2 | 19.2 | 3 | 1.9 | 1.9 | 40 | 2.3 |

| 12 | 190 | 13 | 15 | 8 | 4 | 17.2 | 3 | 1.9 | 1.9 | 40 | 2.3 |

| 13 | 201 | 5 | 14.1 | 8 | 4 | 16 | 2.10 | 1.9 | 1.9 | 40 | 2.3 |

| 14 | 216 | 7.6 | 11.3 | 6 | 2 | 17.3 | 2.10 | 1.9 | 1.9 | 40 | 2.3 |

| 15 | 204 | 8.3 | 13.2 | 6 | 4 | 13.2 | 2.11 | 1.9 | 1.9 | 40 | 2.3 |

| 16 | 217 | 9.9 | 14.1 | 7 | 4 | 15.2 | 2.11 | 1.9 | 1.9 | 40 | 2.3 |

| 17 | 211 | 8.6 | 13.2 | 8 | 2 | 16 | 3.1 | 1.9 | 1.9 | 40 | 2.3 |

| 18 | 221 | 9.3 | 13.1 | 4 | 2 | 16.3 | 2.7 | 1.9 | 1.9 | 40 | 2.3 |

| 19 | 225 | 11.9 | 12.3 | 3 | 6 | 20.2 | 2.11 | 1.9 | 1.9 | 40 | 2.3 |

| 20 | 186 | 7.6 | 13.2 | 4 | 2 | 15 | 2.10 | 1.9 | 1.9 | 40 | 2.3 |

| 4118 | 166 | 287.1 | 89 | 67 | 376.1 | 58.6 | 36.10 | 36.7 | 7 80 | 4.7 | |

| 21 | 174 | 7 | 13.1 | 3 | 2 | 13 | 3.1 | 1.6 | 1.6 | 40 | 2.3 |

| 22 | 181 | 7.3 | 12.2 | 2 | 4 | 15 | 2.10 | 1.6 | 1.6 | 40 | 2.3 |

| 23 | 188 | 8 | 14 | 3 | 2 | 17 | 3 | 1.6 | 1.6 | 40 | 2.3 |

| 24 | 191 | 6 | 14.2 | 4 | 2 | 16.3 | 3 | 1.6 | 1.6 | 40 | 2.3 |

| 25 | 181 | 8 | 13.3 | 4 | 0 | 14.2 | 2.11 | 1.6 | 1.6 | 40 | 2.3 |

| 26 | 163 | 7.3 | 14.1 | 4 | 2 | 13 | 2.10 | 1.6 | 1.6 | 40 | 2.3 |

| 27 | 180 | 7.9 | 16.1 | 5 | 4 | 16.1 | 2.11 | 1.6 | 1.6 | 40 | 2.3 |

| 28 | 180 | 4 | 14.2 | 4 | 4 | 14.1 | 2.10 | 1.6 | 1.6 | 40 | 2.3 |

| 29 | 182 | 5.3 | 13 | 3 | 2 | 11 | 3.1 | 1.6 | 1.6 | 40 | 2.3 |

| 30 | 185 | 4 | 15.2 | 2 | 4 | 14.2 | 2.11 | 1.6 | 1.6 | 40 | 2.3 |

| Total | 5923 | 230.6 | 428.3 | 125 | 93 | 521.2 | 87.11 | 53.10 | 53.7 | 11 80 | 5.12.2 |

In the whole month, therefore, the hospital bought 5923 rotoli of bread, about 230 rotoli of meat (about 204 kg), 428 chickens, 521 quarts of wine (about 218 litres), 87 rotoli of oil (about 69 kg), 53 rotoli of pasta and an equal amount of semolina (about 42 kg). Daily, between two and four ounces were spent on the purchase of foodstuffs (including the purchase of wood and coal and the rations provided for the hospital staff); in detail, meat was bought at one tarì per rotolo, a sandwich at two grani, a hen at two tarì and 16 grani, a quart of wine at about ten grani, oil at one tarì and ten grani per roll and an egg at three grani. For vinegar, salad, and spices –the quantity of which is not specified– about one tarì and ten grani was spent daily.[15] Table 3 details the daily expenditure for June 1685 on food rations purchased for patients and hospital staff.

| 1 June | 4.10.16.1 ½ | 11 | 2.28.5.1 ½ | 21 | 2.26.16.41/2 |

| 2 | 3.28.19.1 ½ | 12 | 3.4.13.4 ½ | 22 | 2.28.15.1 ½ |

| 3 | 3.11.3.1 ½ | 13 | 2.24.18.1 ½ | 23 | 2.28.13.1 ½ |

| 4 | 3.6.3.1 ½ | 14 | 3.1.16.1 ½ | 24 | 3.3.2.4 ½ |

| 5 | 3.18.7.1 ½ | 15 | 3.6.11.1 ½ | 25 | 2.27.10.4 ½ |

| 6 | 3.18.14.1 ½ | 16 | 3.0.16.1 ½ | 26 | 2.21.2.1 ½ |

| 7 | 3.17.16.1 ½ | 17 | 3.5.16.4 ½ | 27 | 3.1.1.1 ½ |

| 8 | 3.7.9.4 ½ | 18 | 2.29.6.4 ½ | 28 | 2.21.13.4 ½ |

| 9 | 3.1.19.1 ½ | 19 | 3.12.7.4 ½ | 29 | 2.27.19.4 ½ |

| 10 | 3.12.13.1 ½ | 20 | 2.24.19.1 ½ | 30 | 2.29.4.4 ½ |

The revenues

The hospital's primary source of income was the funds donated by the General Treasury of the Kingdom of Sicily for the maintenance of the sick. Generally, the sum paid ranged between 130 and 225 ounces per month; in only one case, in April 1681, was there a deferred bi-monthly payment[16].

In the first period (September 1680-April 1681), the hospital received 190 ounces monthly from the General Treasury, but in the following months, the payment would decrease by 60 ounces, at least until June 1682. In fact, from October 1681, an income of about 155 ounces was recorded, but this latter figure included 25 ounces from the rent of five hospital-owned houses.[17] Between July and August 1682, the maximum disbursement from the Treasury was recorded, 225 ounces, 23 tarì, and eight grani, while in the three years from September 1682 to August 1685, the income always corresponded to 202 ounces, eight tarì, and 15 grani, but even about this sum, it was sometimes specified that 2 ounces, eight tarì, and 15 grani were included, which the Royal Court paid for the rent of houses intended for housing military personnel.[18]

The hospital was among those categories that enjoyed significant exemptions from paying indirect taxes. The exemptions granted concerned “los mantenimentos de pan, vino y otras cosas para el govierno del los infermos”, and as was customary, they were settled employing the scasciato (literally out of cash). This system provided for the reimbursement of sums paid by the hospital to maintain patients and staff. The payment would have been charged to the city's ordinary budget, outside the hospital's budget, hence scasciato, ex cassia.[19] In the years under review, the hospital recorded the repayment of 288 ounces, 14 tarì and 18 grani, which took place with occasional payments, but not until 1684.[20]

| Month | Amount |

| April 1681 | 51.16.3 |

| January 1682 | 45.10.5 |

| December 1682 | 50.7.5 |

| April 1683 | 44.7.5 |

| December 1683 | 50.7.5 |

| January 1685 | 46.26.15 |

| Total 1680-1685 | 288.14.18 |

Table 4 shows the sums received by St James Hospital between April 1681 and January 1685 out of the budget by the General Treasury of the Kingdom. From the data present, it is easy to verify a certain constancy in the number of payments, which could suggest the presence of a constant number of in-patients and the consequent stability of consumption.

As we have pointed out in the previous paragraph, in 1685, funds were used for the estufas y unciones deriving from selling vacant ecclesiastical seats. In fact, on 21st June 1666, a royal dispatch had granted the hospital a sum of 260 annual ounces "asignadas sobre expolios y frutos de Iglesia", for a total of 7336 ounces, seven tarì and 11 grani. Similarly, certain annuities were also granted to the city of Trapani, for a capital sum of 687 ounces to be paid in annual instalments of 60 ounces, and to the city of Mazara (696 ounces and 20 tarì), Chiusa Sclafani (1155 ounces) and Agrigento (1339 ounces and 22 tarì), in annual instalments of 50 ounces.[21]

In fact, the payment of the instalments rarely took place punctually, and in many cases, a sum considerably lower than that due was collected; however, this is not an exception, considering the deep economic crisis that affected the entire island in the 1680s, so much so that ecclesiastical bodies, which until the first decades of the 17th century had invested many resources in loans to the State, cities and barons, were forced to contract debts to make up for the shortfall in income (Cancila, 1993: 55).

Only Spanish soldiers received free treatment at the hospital, while all other soldiers had to pay a fee for hospitalization. Among the income items, we find the sums paid by the Burgundians, the Viceroy's guards, the Germans, and the Castellammare (defensive castle settled at the entrance of the port) soldiers.[22] Among the military personnel, only the Castellammare soldiers guaranteed a more regular income, at least in the years 1680-1683.

On average, the monthly income was equivalent to 2 ounces and 15 tarì, except for June 1681, when a payment of 3 ounces and 24 tarì was recorded, and April 1685, when the sum paid was 4 ounces, ten tarì, but most probably considering missing payments from previous months. Finally, the income from payments by non-Spanish soldiers includes that made by a confident Don Augustin, a veteran, who in July 1682 paid 3 ounces and 22 tarì “para curarse en este hospital”.[23]

Additional income came from the sale of offal to the cook. Especially in the three years 1683-1685, the sale of higadillos y pescuezos (literally chicken livers and necks), guaranteed a substantial profit of 32, 35 and 24 ounces respectively, compared to 5 in 1680 and 2 in 1685. In 1684, however, there has yet to be a record of this item. Other income from commercial activities was ensured by the sale of bread and the clothes of the dead. The church adjacent to the hospital boasted a mill, which it probably used for bread-making. However, income was small (just over one ounce), occasional, and absent in the three years of 1682-1684. Clothes were sold at ten tarì and five grani. However, even this is a sporadic phenomenon: it occurs –over the entire five-year period– only four times, and in only one case is the number indicated (12 in March 1681), while the other three are generically annotated unos (a few).[24]

Regarding the administration, however, the accounts clearly show that the most significant income came from the General Treasury endowments (so much so that in 1684, it accounted for 98% of income) and that the expenses were those reported as ordinary and extraordinary, which accounted for between 48% and 55% of income. It is evident, therefore, that any other form of revenue, beyond the subsidy from the Treasury, was derisory. In this sense, there is a symmetry with the OspedaleGrande e Nuovo in Palermo, whose primary sources of income were the endowments of the Citizen Senate.[25] Even the smaller hospital of San Bartolomeo, which was permanently closed at the beginning of the 19th century, based its livelihood on funds allocated by the city administration.[26]

Of all the revenue items examined (see Table 5), only the annuities on the communities and the proceeds from the stripping of vacant ecclesiastical sees represented –but in only two years– a considerable percentage: approximately 24% in 1680 and 22% in 1681. Nevertheless, the same rents were at most 3% in the following three years.

| Anno | Renditee sedi vacanti | Tesoreria generale | Soldati“non spagnoli” | Vendite, censi e affitti | franchigie | Altro | Tot |

| 1680 | 261.20 (24,07%) | 760 (70,04%) | 30.9 (2,76%) | 14.2 (1,29%) | - | 19.18.3 (1,75%) | 1085.19.3 |

| 1681 | 604.22.8 (22,35%) | 1883.10.4 (69,68%) | 47.5 (1,73%) | 67.22.11 (2,47%) | 51.16.3 (1,88%) | 48 (1,77%) | 2702.18.7 |

| 1682 | 16.20 (0,64%) | 2228.2.4 (90,09%) | 48.28.5 (1,94%) | 45.25.14.3 (1,81%) | 95.17.10 (3,84%) | 38.21.4 (1,53%) | 2473.24.17.3 |

| 1683 | 170.24 (6,19%) | 2427.14 (87,87%) | 22.3 (0,80%) | 27.26.15 (0,97%) | 94.14.10 (3,40%) | 20.6.6 (0,72%) | 2762.28.11 |

| 1684 | 30.19 (1,21%) | 2427.14 (98,57%) | 4.25 (0,16) | - | - | - | 2462.28 |

| 1685 | 30 (1,75%) | 1618.10 (94,45%) | 9.10.13 (0,52%) | 5.14.4 (0,29%) | 46.26.15 (2,68%) | 3.5 (0,17%) | 1713.6.12 |

The expenditures

The income analysed so far was, in many cases, barely sufficient to support the expenses necessary for the hospital's proper functioning, which consisted of the payment of salaries, the daily purchase of foodstuffs, and the occasional purchase of wood, coal and all those materials necessary for the maintenance of the structure; a constant expense was also incurred for the payment of the apothecary, who was responsible for supplying the hospital with medicines useful for the care of the sick[27]. Not all officials received a salary; the deputies, for example, received no remuneration, but only “el buen zelo de asistir al referido Hospital y al Real servicio de Su Magestà”, as did the judge.[28]

| Task | Monthly salary |

| Maggiordomo | 10 |

| Rationale | 4.24 |

| Coadjutor of rationale | 1 |

| Guardaroba | 4.24 |

| Massaro | 1 |

| Notary | 5 |

| Doctor | 10 |

| Nurse | 1.6 |

| Pratico (surgeon) | 1.6 |

| Corcamalati | 1 |

| Dispensero | 0.24 |

| Maestro d’Acqua (plumber) | 0.3 |

| Remediante | 1 |

| Cook | 1.6 |

| Servant | 1.4 |

| Chaplain of the infirmary | 1.18 |

| Chaplain of San Giacomo | 1.6 |

Not all salaries were paid by the hospital administration; the rationale, as a member of the military administration, was paid directly by the Senate of the city of Palermo, as was the maggiordomo, whose monthly salary of 10 ounces was paid to him as captain. On the other hand, the guardarobaesattore (bailiff and revenue, in addition to the 4 ounces and 24 tarì paid entirely "en la librança general", received a further 12 tarì per month from the hospital.

The salary paid in full by the hospital was due to the doctor (10 ounces), the coadjutor of the rationale (1 ounce), the chaplain of the infirmary (1 ounce and 18 tarì per month plus a daily ration of 2 tarì, two grani), the chaplain of the church of San Giacomo (1 ounce and six tarì per month plus the same daily ration) and, finally, the notary (5 tarì per month).[29]

Most of the servants received both a monthly salary and a daily ration. The nurse and the practico received 1 ounce and six tarì per month, plus two tarì, two grani per day; the dispensero y comprador 24 tarì per month and two tarì and 12 grani per day. All the other servants were paid a monthly salary of 12 tarì and a daily ration of 1 tarì and six grani, except the maestro d’acqua (3 tarì and ten grani per month), the kitchen boy and the servant, who received no salary but only the ration, the former one tarì and the latter one tarì and six grani respectively. An analysis of the expenses shows that in 1680 about 151 ounces were used to pay wages, divided into two items, one for September (92 ounces and 12 tarì) and one for December (59 ounces, nine tarì and six grani). The following year, on the other hand, there were only 59 ounces, 16 tarì and two grani, of which about 35 were allocated to “los salarios de la familia”.[30] Even less was allocated to wages in 1682 (47 ounces), while in 1683, there were 214 ounces, 22 grani, and 12 tarì: about 80 ounces in February alone, 41 of which were for family wages, which would be paid again in June (35 ounces and 20 tarì) and December (about 52 ounces). Finally, in 1684 and 1685, 39 and 74 ounces, respectively, were allocated to wages.[31]

Wages were, therefore, not paid regularly, and it was not unusual for advance payments to be made and for wages to be paid only at the end of the service or even at the employee's death. This explains the hospital's debt to the servants and officers over the five-year period, which amounted to 2266 ounces, four tarì, and ten grani; of all the wage-earners, only the coadjutor of the rationale, the servant and the maestro d’acqua had no claims, while the most considerable sum was owed to the apothecary (1274 ounces, 12 tarì, and seven grani), who nevertheless received almost regularly 40 ounces per month: an instalment that the hospital paid to repay the sums he advanced for the purchase of medicines. It should also be pointed out that the wages of the guardaroba and the cook were included in the item extra-ordinary meal.[32]

The item gasto ordinario y extraordinario, present every month –except March and August 1681 and July 1685– certainly included the expenses incurred for foodstuffs (ordinary) and the payment of certain wages (extraordinary). However, the expenses incurred for foodstuffs did not include those for purchasing hens; in fact, payments to gallineros were listed individually and constituted one of the most frequent items in the entire five-year period. The highest sum is recorded in August 1684 (70 ounces, 17 tarì and ten grani) to pay for 814 hens purchased in June; the lowest is recorded in June 1683 (16 ounces, 19 tarì and four grani), but in this case the number is not specified.

As for the expenses considered extraordinary, on the other hand –referring to the Suma del gastoextraordinario que se ha hecho en el mes de junio 1685 reported in the register– we can deduce that in most cases these were sums paid for repairs or the purchase of materials necessary for the maintenance of the building:

“A 2 de dicho mes a Pedro Torralva 3 tarines por 8 oncias de hilas 3.12.3

A 3 de dicho mes a Ana Miliana se le pagaron 2 tarines y 10 granos por 6 oncias de hilas que entrego 2.10

A 11 de dicho mes a Ana Miliana 2 tarines y 10 granos por 6 oncias de hilas a razon de 5 tarines a rotulo 2.10

A 11 de dicho mes a Mastro Francesco Priche, serraxero, 3 onzas y 2 tarines por haver limpiado y acomodado los hierros de la zirufia 3.2

A 11 de dicho mes al guardaropa por haver accomodato la garrafa grande de la la enfermeria 3 tarines y 2 granos 3.2

A 13 de dicho mes a Melchior Escanavino 27 tarines y 10 granos por la hechura de 27 colchones a razon de 14 granos el uno y 10 jergones y 16 almuadas 27.10

A 14 de dicho mes a Thomas Lascio 2 tarines por haver parado los bancos para la comunion de los cavalleros por la Pentecoste 2

A 14 de dicho mes al guardaropa por haver sacado una partida de la tabla y cobrado las onzas 10 (...) 3.6

A 15 de dicho mes a Isabel Redondo 7 tarines y 19 granos por un rotulo y 7 oncias de hilas para la zirufia

A 16 de dicho mes al sergento Marco Tavallos 20 tarines por haver acomodato la casa en que vive 20

A 17 de dicho mes al guardaropa 12 tarines per su salario que se paga cada mes 12

A 30 de dicho mes al cocinero Antonio Polito 12 tarines por su salario 12

Al dicho cocinero 12 tarines por 2 cuchillas y un mattero de marmol 12”

Some expenses that could have been included under gasto ordinario y extraordinario were instead listed individually. The most significant was the purchase of tin, wood, coal, and whatever was needed to make new beds and curtains for the sick rooms or repair the windows or the water conduit in the garden.

Finally, it highlights the expenses related to religious events. In April 1681, for example, about 6 ounces were spent on the celebration of Maundy Thursday and three on the decoration of the church, and in July of the same year, 17 ounces and 26 tarì were spent on the celebration of St James. In 1682, the Maundy Thursday celebration (this time in March) would have cost 4 ounces more than the previous year, while in 1683, the Sepulchre expenses amounted to 15 ounces, 26 tarì and 16 grani. On the other hand, a much smaller sum (4 ounces, 14 tarì, and eight grani) was allocated in 1684 for dinner offered to the officers of the Tavola Pecuniaria of Palermo on Candlemas Day, while in June of 1685, no less than 40 ounces were used “por la fiesta y acomodar la Yglesia”.[33]

A slightly more complex situation concerning expenditure can be seen. In addition to the ordinary and extraordinary expenditures, the sums allocated to the purchase of chickens and those used to pay the apothecary constituted a considerable percentage (between 13 and 20.94% for the former and about 18% for the latter).

Conversely, wages represented a decidedly low percentage (between 2 and 7%), with the sole exception of 1680 (around 17%). The remaining items, indicated in the successive table as “other,” in 1681 and 1685, due to an increase in expenses incurred for the purchase of wood, coal, tin, and cloth, amounted to as much as 346 in the first year (13%) and 322 in the second (17%).

| Year | Chickens | Ordinary and Extra-ordinary expenses | Apothecary | Salaries | Other | Total |

| 1680 | 117.15.8 (13,43%) | 422.5.11 (48,45%) | 160 (18,36%) | 151.21.6 (17,33%) | 19.26 (2,18%) | 871.8.5 |

| 1681 | 465.27.10.3 (17,58%) | 1252.8.10 (47,35%) | 520 (19,66%) | 59.16.2 (2,23%) | 346.23.2 (13,08%) | 2644.15.4.3 |

| 1682 | 403.4 (15,98%) | 1346.23.17 (53,39%) | 480 (19,04%) | 47.9.11 (1,86%) | 244.12 (9,67%) | 2521.19.8 |

| 1683 | 405.1.15 (15,01%) | 1439.1.16 (53,33%) | 510 (18,90%) | 214.22.12 (7,93%) | 130.3.16 (4,81%) | 2698.29.19 |

| 1684 | 494.17.12 (20,09%) | 1416.11.6 (57,60%) | 440 (17,90%) | 39.19 (1,58%) | 68.8.8 (2,76%) | 2458.26.6 |

| 1685 | 298.2.13 (16,05%) | 840.24.3 (45,25%) | 320 (17,24%) | 74.16.6 (3,98%) | 322.21.13 (17,34%) | 1856.21.13 |

In addition, a comparison of the annual values of income and expenditure makes it possible to draw up a balance and thus verify for each year whether the balance was positive or negative:

| Year | Incomes | Expenditures | Balance |

| 1680 (Sept.-Dec.) | 1085.19.3 | 871.8.5 | 214 |

| 1681 | 2702.18.7 | 2644.15.4 | 58 |

| 1682 | 2473.24.17 | 2521.19.8 | - 48 |

| 1683 | 2762.28.11 | 2698.29.19 | 64 |

| 1684 | 2462.28 | 2458.26.6 | 4 |

| 1685 (Jan.-Aug.) | 1713.6.12 | 1856.21.13 | - 143 |

| Tot. 1680-85 | 13201.5.10 | 13152.0.15 | 49 |

The partial balances only show negative values in the years 1682 and 1685, of 48 and 143 ounces, respectively; in the first case, one could attribute the negative balance to a net decrease in income from rents and the selling of vacant seats (16 ounces compared to approximately 600 in the previous year); in the second, the negative balance is probably caused –as we have already pointed out– by a considerable increase in the expenses incurred for the purchase of wood (36 ounces), coal (70 ounces) and cloth (85 ounces). However, the balance is in surplus in the other three years, with a minimum value (4 ounces) only in 1684.

Even for the entire five-year period, the budget shows a positive balance, with a surplus of approximately 49 ounces; the total income amounted to 13201 ounces, five tarì, ten grani and the revenue to 13152 ounces, 15 grani.[34] It follows, therefore, that the income made it possible to cover the ordinary expenses of care and management of the entire hospital but that, in the event of an increase in extraordinary expenses, a surplus of only 49 ounces would not have made it possible to cope with the financial emergency.

The “human accounting”

Special consideration must be given to the reference in the Relaciondelo Deputatos que oy tiene el Hospital Real de Santiago delos Españoles de la ciudad de Palermo to the number of hospitalized and cured patients. The June monthly report for the year 1685 shows the number of in-patients in the morning and evening. This data constitutes a highly significant element in the Hospital of San Giacomo management model since the human element is also included in the documentation produced by the administration to account for its work. On the one hand, “human accounting” would have a double reason to demonstrate to the viceroy the effectiveness of the hospital's administrative action with the correct allocation of the resources received. On the other, one could hypothesize an attempt to accountability the hospital towards the care provided, thus trying to prove its effectiveness (Funnell et al., 2017: 1111-1141). The emergence of medicine as a systemic science, not an evolution of the empiricism that had characterized it in previous centuries, and the formalization of medicine itself into a disciplined corpus is, according to Foucault, to be traced back to the caesura processes of the American and, above all, French revolutions. From the era of taxonomy, we pass to a historical-organic era in which the clinic is no longer merely the result of the observation of reality but a valid theory of knowledge (Foucault, 2003: 46-54).

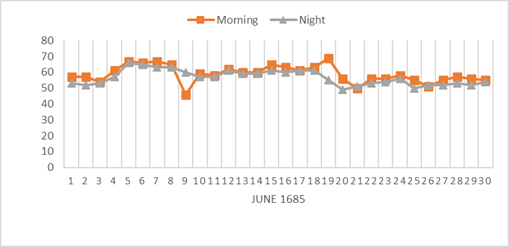

Graphic 1

Royal Hospital of San Giacomo, number of inpatients

Author's elaboration on AGS data, SP, libro 716

Graph 1 shows the trend in the number of inpatients in the morning and evening, highlighting the systematic decrease in the number of inpatients at the end of the day, suggesting that daily treatments are being carried out. Only in three cases, on 9, 21, and 26 June, were there more inpatients present in the evening than in the morning, with the maximum reached on day 9 of 14 more inpatients.

Conclusions

The data analysed so far allows some considerations regarding the functioning of the Hospital of St James. In the first place, the internal organization is typical of modern-day welfare structures: financial management is entrusted to the officers, the care of the sick is ensured by an adequate presence of medical and paramedical staff, and pastoral care by the chaplains, as provided for in the directives issued in the Capitoli (rules) of the Ospedale Grande of Palermo founded in 1442.[35] In addition, the servants present - from the dispensero to the coricamalati, to the remediante, followed the sick from the moment they entered the hospital, and ensured the order and cleanliness of the building, as found, for example, in the hospital of San Bartolomeo in Palermo and Santa Maria la Pietà in Messina and Santa Caterina in Monreale (Barranco, 1991: 95; Sambito, 1991: 15-23; Rossi, 2014: 285-308).

This first analysis of the hospital of San Giacomo makes it possible to clearly identify the separation between institutions of care and those of cure, eliminating the overlap that had distinguished them since the Middle Ages. Secondly, the role exercised by the ecclesiastics, previously dedicated to the care of both bodies and souls, is significantly reduced. In the 17th century, it was evident that the function of religious personnel within the hospital was limited to spiritual care only. Finally, there is a clear definition of the hospital's internal organizational functions, with the division of care activities from administrative ones, according to an organizational line that would see its definitive formalization in the following century.

To conclude, given the surviving archival evidence, this work has no aim of exhaustiveness, nor can the case of the Hospital of San Giacomo degli Spagnoli in Palermo be used as a reference study. Instead, Palermo's military hospital could represent an attempt to analyse the organizational and administrative systems and models of military care institutions in the modern age - albeit starting from a very circumscribed case - with a reading key not directed at reconstructing their economic performance, but rather at highlighting those elements that characterize their organizational structure (Hopwood, 1990: 7-17).

Acknowledgments

I appreciate the comments of the anonymous reviewers

Referencias bibliográficas

Aymard, M. & Bresc, H. (1975). Nourritures et cosommation en Sicile entre XIV et XVIII siècle. Annales Économies Sociétés Civilisations, 2-3, 596.

Barranco, M. (1991). Strutture ospedaliere a Messina tra ‘700 e ‘800. L’ospedale Santa Maria La Pietà, in C. Valenti (Edit.), Struttura e funzionalità delle istituzioni ospidaliere siciliane nei secoli XVIII e XIX. Salute e Società, (pp.80- 95). Centro italiano di storia sanitaria e ospedaliera.

Bigoni, M., Deidda Gagliardo, E., Funnell, W. (2013). Rethinking the sacred and secular divide. Accounting and accountability practices in the Diocese of Ferrara (1431-1457). Accounting, Auditing & Accountability Journal, 26(4), 567-594.

Boccadamo, G. (2000). Maria Longo, l’ospedale degli incurabili e la sua insula, Campania Sacra, 30, 70-93.

Bonaffini, G. (1980). Per una storia delle istituzioni ospedaliere a Palermo tra XV e XIX. Ila Palma.

Cancila, O. (1983). Baroni e popolo nella Sicilia del grano. Palumbo.

Cancila, O. (1993). Impresa redditi mercato nella Sicilia moderna. Palumbo.

Cipolla, C.M. (1985). Contro un nemico invisibile. Epidemie e strutture sanitarie nell’Italia del Rinascimento. Il Mulino.

Corrao, P. (2013). I Maestri Razionali e le origini della magistratura contabile (secc. XIII-XV). In Storia e attualità della Corte dei Conti, (pp. 31-46). Associazione no-profit Mediterranea.

Di Blasi, G.E. (1842). Storia cronologica dei viceré luogotenenti e presidenti del regno di Sicilia. Oretea.

Emanuele e Gaetani, F.M. (1875). Il Palermo d’oggigiorno. In G. Di Marzo (Edit.), Biblioteca storica e letteraria di Sicilia, (pp. 310-361). Luigi Pedone Lauriel.

Foucault, M. (2003). The Birth of the Clinic: An Archaeology of Medical Perception. Routledge.

Funnell, W., Antonelli, V., D’Alessio, R., Rossi, R. (2017). Accounting for madness: the “Real Casa dei Matti” of Palermo 1824-1860, Accounting, Auditing & Accountability Journal, 30(5), 1111-1141.

Giuffrida, A. (1975). Considerazioni sul consumo della carne a Palermo nei secoli XIV e XV, Melanges de l’Ecole Français de Rome. Moyen Age-Temps modernes, 87(2), 583-595.

Giuffrida, A. (2011). La Tavola e il Monte di Pietà di Palermo tra crisi e sperimentazione (1778-1799). In Giuffrida, A., D'Avenia, F., Palermo, D., (Edit.), Studi Storici dedicati a Orazio Cancila, (pp. 1053-1086). Mediterranea -Associazione no profit.

Gracia Rivas, M. (2006). Los Hospitales Reales del Ejército y Armada en las campañas militares del siglo XVI. In García Hernán, E., Maffi, D., (Edit.), Guerra y Sociedad en la Monarquía Hispánica. Política, Estrategia y Cultura en la Europa Moderna (1500-1700), vol. II, (pp. 765-784). Ediciones del Laberinto.

Hopwood, A.G. (1990). Accounting and Organisation Change, Accounting, Auditing and Accountability Journal, 3(1), 7-17.

Macrì, G. (2007). I conti della città. Le carte dei razionali dell’Università di Palermo (secc. XVI-XIX). Quaderni di Mediterranea.

Mantelli, R. (1986). Il pubblico impiego nell’economia del Regno di Napoli. Retribuzioni, reclutamento e ricambio sociale nell’epoca spagnuola (secc. XVI-XVIII). Istituto italiano per gli Studi Filosofici

Mazzè, A. (1998). L’edilizia sanitaria a Palermo dal XVI al XIX secolo, Parte Seconda. Accademia Nazionale di Scienze Lettere e Arti di Palermo.

Novi Chavarria, E. (2020). Accogliere e curare. Ospedali e culture delle nazioni nella Monarchia ispanica (secc. XVI-XVII). Viella.

Picardi, N. (2010). Birth in Rome of the first hospital in the history of Europe. Further development of the Roma’s Hospitals, AnnaliItaliani di Chirurgia, 81, 329-335.

Pidone, G. (1834). Descrizione del Real Ospedale militare di Palermo e della sua interna amministrazione. Tip. F. Spampinato.

Reinarz, J. (2016). Towards a History of Hospital Food, Food & History, 14(1), 1-12.

Riva, M.A., Cesana, G. (2013). The charity and the care: the origin and evolution of hospitals, European Journal of Internal Medicine», 24(1), 1-4.

Rossi, R. (2014). Organizzazione, amministrazione e gestione delle strutture sanitarie nella Sicilia di età moderna: l’ospedale di Santa Caterina pro infirmis di Monreale tra XVI e XVII secolo, Mediterranea. Ricerche Storiche, 31(2), 285-308.

Sambito, S. (1991). Le strutture sanitarie a Palermo tra la fine del secolo XVIII e i primi del XIX. In Valenti, C., (Edit.), Struttura e funzionalità delle istituzioni ospidaliere siciliane nei secoli XVIII e XIX. Salute e Società, (pp. 15-23). Centro italiano di storia sanitaria e ospedaliera.

Santoro, D (2006). Lo speziale siciliano tra continuità e innovazione: capitoli e costituzioni dal XIV al XVI secolo, Mediterranea. Ricerche storiche, 8(2), 465-484.

Stevens Crawshaw, J.L. (2012). Plague Hospitals. Public health for the City in Early Modern Venice. Ashgate.

Storrs, C. (2006). Health, Sickness and Medical Services in Spain's Armed Forces c.1665-1700, Medical History, 50(3).

Notes

“A hospital should be sufficiently spacious both to allow the beds to be laid out in rows, thus enabling the doctors, surgeons and other hospital staff to move freely between them and properly minister to their patients. In addition, each ward should have sufficient windows for proper ventilation – in order to disperse the bad odour from the patients' wounds and admit fresh air – and lighting. The building should also have water” (Storrs, 2006: 53).

“But medicines were not the only means to aid the sick., Another important aspect of the treatment was, inevitably, the diet. According to a contract agreed in the spring of 1696, those officers and men sent to the royal hospital at Barcelona in the Convento de Jesús were to receive nine ounces of meat a day – six at lunch and three at dinner – cooked and well seasoned with parsley, saffron and vegetables appropriate to the patient (as prescribed by the doctor). Those for whom this was not appropriate would be given chicken or some other substitute. In addition, patients would receive an allowance of wine” (Storrs, 2006: 59).

| Year | Incomes | Expenditures |

| 1680 | 926.26 | 980.3.13 |

| 1681 | 2746.17.8.3 | 2731.9.17.3 |

| 1682 | 2536.19.11.3 | 2518.20.8 |

| 1683 | 2772.29.11 | 2621.16.17 |

| 1684 | 2426.29 | 2464.28 |

| 1685 | 1790.24.9 | 1833.21.4.3 |